Reginald Joseph Mitchell was a British aircraft designer who worked for the Southampton aviation company Supermarine from 1916 until 1936. He is best known for designing racing seaplanes, such as the Supermarine S.6B, and for leading the team that designed the Supermarine Spitfire.

Reginald was born on May 20, 1895, in Staffordshire, England. He was the second eldest of five children and the eldest of three brothers. His father, Herbert Mitchell, was a Yorkshireman who became the headmaster of three Staffordshire schools in the Stoke-on-Trent area before retiring from teaching. He then helped establish a printing business, Wood, Mitchell and C. Ltd, in Hanley.

Reg, as he was known to his family, started attending Queensberry Road Higher Elementary School at the age of eight. He later moved on to Hanley High School, where he discovered his passion for making and flying model aircraft. In 1911, at the age of 16, he left school and started working as an apprentice at Kerr Stuart & Co. of Fenton, a railway engineering works. Upon completing his apprenticeship, he joined the drawing office at Kerr Stuart while also pursuing studies in engineering and mathematics at a local technical college, where he demonstrated a strong aptitude for mathematics.

After leaving Kerr Stuart in 1916, Mitchell worked as a part-time teacher for a while. He tried to join the armed forces twice but was rejected both times due to his engineering training.

Later that year, Mitchell joined the Supermarine Aviation Works in Southampton, possibly for a probationary period. Since its formation in 1912, the company has specialized in building flying boats, producing its first aircraft, the Pemberton-Billing P.B.1, in 1914. During the First World War, Supermarine was taken over by the British Government. During this period, the company produced the first British single-seat flying boat fighter, the Supermarine Baby.

Upon joining the company, Mitchell had the opportunity to develop skills in various roles to gain experience in the aircraft industry. His background in engineering helped him transition from working with locomotives to understanding aircraft. Mitchell, who was a competent mathematician, was recognized for his ability to think creatively and use his intuition when analyzing designs. The earliest record of his work at Supermarine is as a draughtsman dating back to 1916. By 1917, he had become the assistant to the company's owner and designer, Hubert Scott-Paine. He likely played a role in the development of the Baby, which was later adapted for racing for the Schneider Trophy in 1919 and renamed the Supermarine Sea Lion.

In 1918, Mitchell was promoted to become the works manager's assistant. Supermarine's chief designer William Hargreaves left the company in the summer of 1919, and Mitchell took up his new duties later that year, leading a team that had consisted of six draughtsmen and a secretary in 1918. Following his promotion, the 19-year-old returned to Staffordshire and married his fiancée Florence Dayson, an infant school headmistress who was 11 years his senior. By 1921, he had become Supermarine's chief engineer. Following the departure of Scott-Paine in November 1923, Mitchell negotiated a new contract, which led to greater influence in the company. The 10-year contract was a sign of his indispensability to Supermarine.

It is not clear how Mitchell was quickly promoted at a young age, as few documents about his early career have survived. However, it was not uncommon for young men like Mitchell to be promoted quickly at that time; others his age held similar positions in other aircraft companies. Decades after his death, surviving colleagues at Supermarine who knew Mitchell were hesitant to share their memories when asked for information about him.

Between 1920 and 1936, Mitchell designed 24 airplanes. In 1920, he adapted the Supermarine Channel to create the Commercial Amphibian, which was praised for its design and reliability. He also redesigned the Supermarine Baby into the Supermarine Sea King. Additionally, he modified a Channel for the Chilean government and created the Supermarine Sea Eagle in 1922.

In the early years of his career, Mitchell designed innovative aircraft such as the Supermarine Seal II and the Flying Boat Torpedo Carrier. He also created the Supermarine Swan, Supermarine Seagull II, and the Amphibian Service Bomber, later renamed the Supermarine Scarab, which was used by the Spanish Navy until 1928.

Supermarine's first land aircraft design, the Supermarine Sparrow, did not succeed in the Air Ministry's Light Air Competition of 1924 and did not receive any orders. A modified version, the Supermarine Sparrow II, was utilized by Mitchell to experiment with various airfoil designs.

The Supermarine Southampton was developed in March 1924, and its improved version, the Southampton II, with a metal hull, flew for the first time in 1927. The aircraft proved to be successful and was used by six RAF squadrons until 1936, establishing Britain as a leader in maritime aircraft development.

In 1926, the Air Ministry issued specification 21/26 to address the need for new fighter aircraft. Mitchell's design team, reorganised into separate drawing and technical offices, responded with several designs, including the Single Seat Fighter. Supermarine shifted its focus from wooden amphibious aircraft to larger metal flying boats, such as the 3-engined Biplane Flying Boat designed in November 1927. Additionally, the company introduced the Supermarine Air Yacht and a new design, the Southampton X (unrelated to other planes with the same name), which was ordered in June 1928. Mitchell simplified the design of the Air Yacht and the Southampton X, opting for less complex curved surfaces and resulting in an appearance that was described as "boxy" for these aircraft.

Specification R.6/28 was issued in 1928, leading to a series of designs by Supermarine for a six-engined flying boat. One of the designs represented a significant departure for Mitchell— it featured a newly designed 43m cantilever wing with a large surface area and cross-section. However, the aircraft was never built. From 1929 to 1931, Mitchell continued to design aircraft based on the Southampton and the Southampton X, including the Supermarine Sea Hawk and its variant the Sea Hawk II, the Type 179, the Nanok, and the Seamew.

In February 1929, Mitchell submitted patent GB 329411 A for "Improvements in the Cooling System of Engines for Automotive Vehicles," which involved a condenser to be placed within the wings of an aircraft. The Air Ministry initially rejected Supermarine's proposal for such a wing-cooled aircraft, but in May 1929, a new specification allowed Mitchell to revisit his ideas. A similar patent was submitted in 1931. The condenser was used in the Type 232, produced in April 1934, although this model was never put up for tender.

In the early 1930s, many of Mitchell's ideas never made it past the early design stages. Supermarine attempted to sell a 5-engined flying boat, but the contract was cancelled in early 1932, resulting in job losses and wage cuts. However, in 1933, the company's fortunes turned around when it received an order for 12 Scarpas (previously the Southampton IV) under the specification R.19/33, marking the first contract for a new design by Mitchell since 1924. This order was followed by orders for the Supermarine Stranraer, which entered production in 1937.

After the first Seagull V flew in June 1933, the Royal Australian Air Force expressed interest and ordered 24 aircraft. That same year, the RAF placed an initial order for 12 aircraft, which were renamed the Supermarine Walrus. After the issuance of Air Ministry specification 5/36, Mitchell began working on a redesigned version of the Walrus, which was named the Sea Otter. Work on the Sea Otter was completed after Mitchell died in 1937, and it made its first flight in September 1938.

Mitchell and his design team collaborated on creating a series of racing seaplanes for the Schneider Trophy competition. The team consisted of Alan Clifton (who later became the head of the Technical Office), Arthur Shirvall, and Joseph Smith. These individuals played a crucial role in Supermarine's success, along with the National Physical Laboratory (NPL), which provided indispensable support, guidance, and scientific expertise through detailed reports. Mitchell's involvement in the competition placed him at the forefront of aviation design.

Mitchell designed the Supermarine Sea King II to be the Sea Lion II, which competed in the 1922 Schneider Trophy in Naples. The Sea Lion II emerged as the winner, achieving an average speed of 145.7 miles per hour.

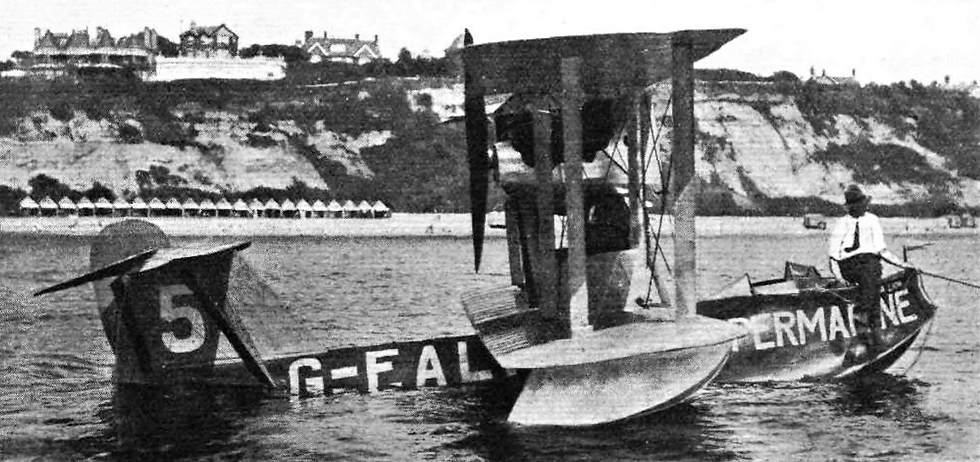

Supermarine didn't have enough time to design a new flying boat for the 1923 competition. So, they borrowed the Sea Lion II back from the Air Ministry and had Mitchell make some changes to it. With the help of D. Napier & Son, they increased its maximum speed by 10 knots, using the 525 horsepower Lion III engine. Mitchell also made modifications to reduce drag forces, such as reducing the wingspan from 32 to 28 feet, modifying the struts, floats, and hull, and changing the way the engines were fitted.

In the 1923 contest, two out of the three British entrants were damaged before the race, leaving the Sea Lion III to compete solo. The United States team, flying Curtiss seaplanes, had a strong performance in the competition. The winning pilot, David Rittenhouse, achieved a top speed of 177.27 miles per hour.

During the modification of the Sea Lion II at the Woolston Works, Mitchell was already working on a new plane. Supermarine recognized that the American monoplane was the best design available at the time. The Supermarine S.4, named by Mitchell with "S" standing for Schneider, was a joint venture between Napier and Supermarine. The Supermarine team had more freedom than American designers, as they were backed by the Air Ministry. The S.4 was considered Mitchell's first outstanding success after his death. He used the practical experience gained from designing its successor, the Supermarine S.5.

Mitchell understood the importance of reducing drag to achieve higher speeds. His new design was a mid-wing, cantilever floatplane. It was similar to a French monoplane, the Bernard SIMB V.2, which had broken the flight airspeed record in December 1924. The S.4 did not have the newly designed surface radiators, which were not available at the time, but it was aerodynamic and aesthetically pleasing. During trials, it reached speeds of 226.742 miles per hour and caused a sensation in the press.

The S.4 crashed before the 1925 race for reasons that were never clearly established. During the navigation trials, it stalled and fell into the sea from 100 feet. The pilot, Henri Biard, was rescued by a launch. Mitchell, who was on board the rescue launch, jokingly asked the injured man, "Is the water warm?"

The Air Ministry, the Society of British Aircraft Constructors, and the Royal Aeronautical Society (RAeS) decided not to challenge for the Schneider Trophy in 1926. However, Mitchell confirmed that Supermarine would be ready for the race. His work at the NPL began in November of that year. Wind tunnel tests at the NPL showed that the S.4's radiators created a third of the aircraft's total drag. Without this, it would have been the most streamlined aircraft in the world. Although British aircraft companies planned to produce entries for the 1926 race, the specifications issued by the Air Ministry made it impossible for any aircraft to be completed and tested in time to be entered.

Two Supermarine S.5 seaplanes were entered in the 1927 contest held in Venice. Mitchell believed that a monoplane on twin floats had lower drag than other aircraft types of that time. Wind tunnel tests at the NPL convinced him to abandon the cantilever wing design as it was too heavy. The NPL also showed that flat-surfaced skin radiators reduced drag better than the corrugated variety preferred by American designers. Mitchell used this finding to improve the S.5. He decreased the fuselage cross-section area by 35% compared to the S.4 and criticized the RAF's pilots for being too large to fit into the resulting S.5's cockpit. Additionally, the fuselage skin thickness was reduced using duralumin.

The two Supermarine S.5s were the only seaplanes to finish the race, coming in first and second. The third British entrant, a Gloster IV, and the three Italian competitors flying Macchi M.52s were forced to drop out of the race. This event was witnessed by the Italian dictator Benito Mussolini and a large crowd gathered on the Venice Lido.

In 1918, Mitchell was elected to the RAeS. He was awarded the society's Silver Medal in 1927. At the end of that year, he took on the role of Technical Director at Supermarine. When Vickers Ltd took over the company in 1928, he continued as Supermarine's chief designer. One of the conditions of the takeover was that he remain in this role for the next five years.

Interest in the competition declined after the 1927 race. There was no competition the following year, as the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale was persuaded by the Royal Aero Club to hold races every two years in the future.

Mitchell believed that a more powerful engine than the Napier Lion was needed for any future aircraft competitions. The Air Ministry asked Rolls-Royce Ltd to create a new engine for Supermarine's new seaplane, now known as the S.6. Rolls-Royce, under pressure to produce an engine that matched the S.6's streamlined shape, chose the partially-developed 825 horsepower Buzzard. Mitchell had to make adjustments to his design to accommodate the larger engine, such as repositioning the forward float struts and redesigning the engine cowling. The Air Ministry ordered two S.6 seaplanes, both of which were built by August 1929. Mitchell had to make modifications to the seaplanes to ensure the engines could operate at maximum power, addressing issues such as inadequate radiators, high engine torque causing the S.6 to move in a circle, and an incorrectly positioned centre of gravity.

In 1929, the race at Calshot was won by Supermarine, with their S.6 achieving an average speed of 328.64 mph. Three out of the four new aircraft were entered by the UK. The older Italian Macchi M.52R came in second, and Supermarine's backup, an S.5, secured third place.

Britain's last plane in the series, the Supermarine S.6B, was the result of Mitchell's efforts to perfect the design of the racing seaplane. It was funded by Lady Houston, a wealthy philanthropist, who donated £100,000 (equivalent to £10 million in 2019) after the British Government chose not to enter an RAF team for the 1931 contest.

Mitchell chose to create an enhanced version of the S.6 while minimizing the number of modifications. The improvements included a more powerful engine, adjustments to accommodate increased engine heat and extra torque, as well as larger quantities of cooling oil and fuel. The S.6B was a bigger seaplane than the S.6, requiring a more efficient cooling system and a sturdier frame.

The S.6B completed the course successfully and won the 1931 race. According to the Schneider Trophy rules, the contest would end when any one country managed to win the trophy three times in five years. As a result of the S.6B's victory, Britain won the contest outright. The aircraft went on to break the world air speed record, reaching a speed of 407.5 miles per hour that year. For his services in connection with the Schneider Trophy contest, Mitchell was awarded the Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (CBE) on 29 December 1931.

In 1930, the Air Ministry issued specification F7/30 for a fighter aircraft suitable for use by both day and night squadrons. Mitchell's proposed design, the Type 224, was one of three monoplane designs developed into prototypes for the Air Ministry. The final design featured an open cockpit, four Vickers machine guns, a 660-horsepower Rolls-Royce Goshawk engine, and a fixed undercarriage. It also included an inverted gull wing, necessary to accommodate the demands of the engine's cooling system. The wing did not have flaps, which were required for the aircraft to land at safe speeds.

Unofficially named the Spitfire, the Type 224 made its first flight in February 1934. The aircraft appeared clumsy and inefficient, partly due to the cooling system's failure to prevent the engine from overheating. The RAF deemed the Type 224's performance unsatisfactory and instead chose the Gloster Gladiator.

While the Type 224 was still under construction in 1933, Mitchell was also working on the design of the Type 300, which would later become known as his masterpiece, the Supermarine Spitfire. Mitchell refined the design of the Type 224, using the same engine but incorporating a shorter wing and a retractable undercarriage. Although the Air Ministry initially rejected Mitchell's design, he modified it by making the wing thinner and shorter, incorporating the newly designed Rolls-Royce Merlin engine, and utilizing an innovative new cooling system. This demonstrated his willingness to accept ideas from others.

Private funding supported design work for a short time, but in December 1934, the Air Ministry commissioned Supermarine to build a prototype based on Mitchell's design. Mitchell didn't agree with the Air Ministry's request to modify the Spitfire to have a tail wheel. At the time, he was unaware that the government had decided to build hard surface runways for the RAF in preparation for future war, which made the modification necessary.

The prototype with serial number K5054 first took flight on 6 March 1936 in Eastleigh, Hampshire. Mitchell observed the flight, even though he was ill and had to travel to Eastleigh during the flight tests for K5054. By June 1936, before the prototype had completed its trials, the Air Ministry had already ordered 310 Spitfires.

Many of the technical advances in the Spitfire were made by people other than Mitchell. For instance, the thin elliptical wings were designed by the Canadian aerodynamicist Beverley Shenstone, and the Spitfire shared similarities with the Heinkel He 70 Blitz. The under-wing radiators had been designed by the Royal Aircraft Establishment, and monocoque construction had been first developed in the United States. Mitchell's achievement lay in merging these different influences into a single design, drawing from his "unparalleled expertise in high-speed flight… and a brilliant practical engineering ability, exemplified in this instance by the incorporation of vital lessons learned from Supermarine's unsuccessful type 224 fighter." The quality of the design enabled the Spitfire to be continually improved throughout World War II.

In 1933, Mitchell underwent a permanent colostomy to treat rectal cancer, which left him permanently disabled. Despite this, he continued to work on the Spitfire and a four-engined bomber, the Type 317. Unusually for an aircraft designer in those days, he took flying lessons. He obtained his pilot's licence and made his first solo flight in July 1934.

In 1936 Mitchell was diagnosed again with cancer, and early the following year was forced by his illness to give up work. In his absence, his assistant Harold Payn led the design team at Supermarine. Mitchell flew to Vienna for specialist treatment and remained there for a month, but returned home after the treatment proved to be ineffective. He died at home in Highfield, Southampton, on 11 June 1937 at the age of 42.

The quality of the flying boats designed by Mitchell for the RAF established him as the foremost aircraft designer in Britain. His obituary published in The Journal of the Royal Aeronautical Society in 1937 described him as "brilliant" and "one of the leading designers in the world". The Society paid tribute to their colleague, describing him as being "a quiet, subtle, not obvious genius" who had "an intuitive capacity for grasping the essentials, getting to the point and staying there". Smith, who became Chief Designer at Supermarine after Mitchell's death, said of him that "He was an inveterate drawer on drawings, particularly general arrangements,... which were usually accepted when the thing was redrawn."

Comments